Thomas Bayrle

fiat

March 17 – April 21, 2018

Reiter und Pferd, 1990

watercolour, Atari computer prints on canvas

166 × 242 cm

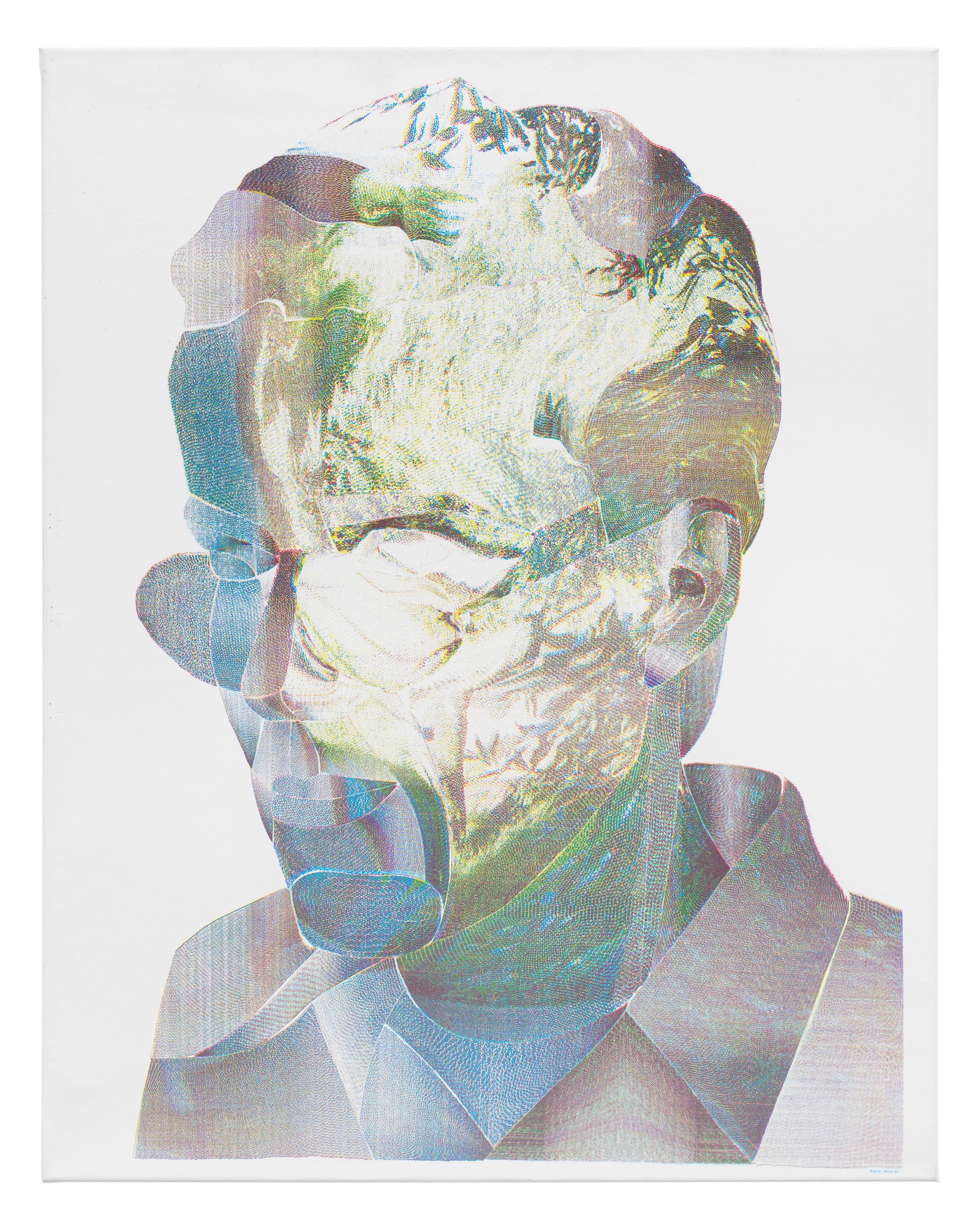

Stefan Mück, 1990

silkscreen print on canvas

100 × 84 cm

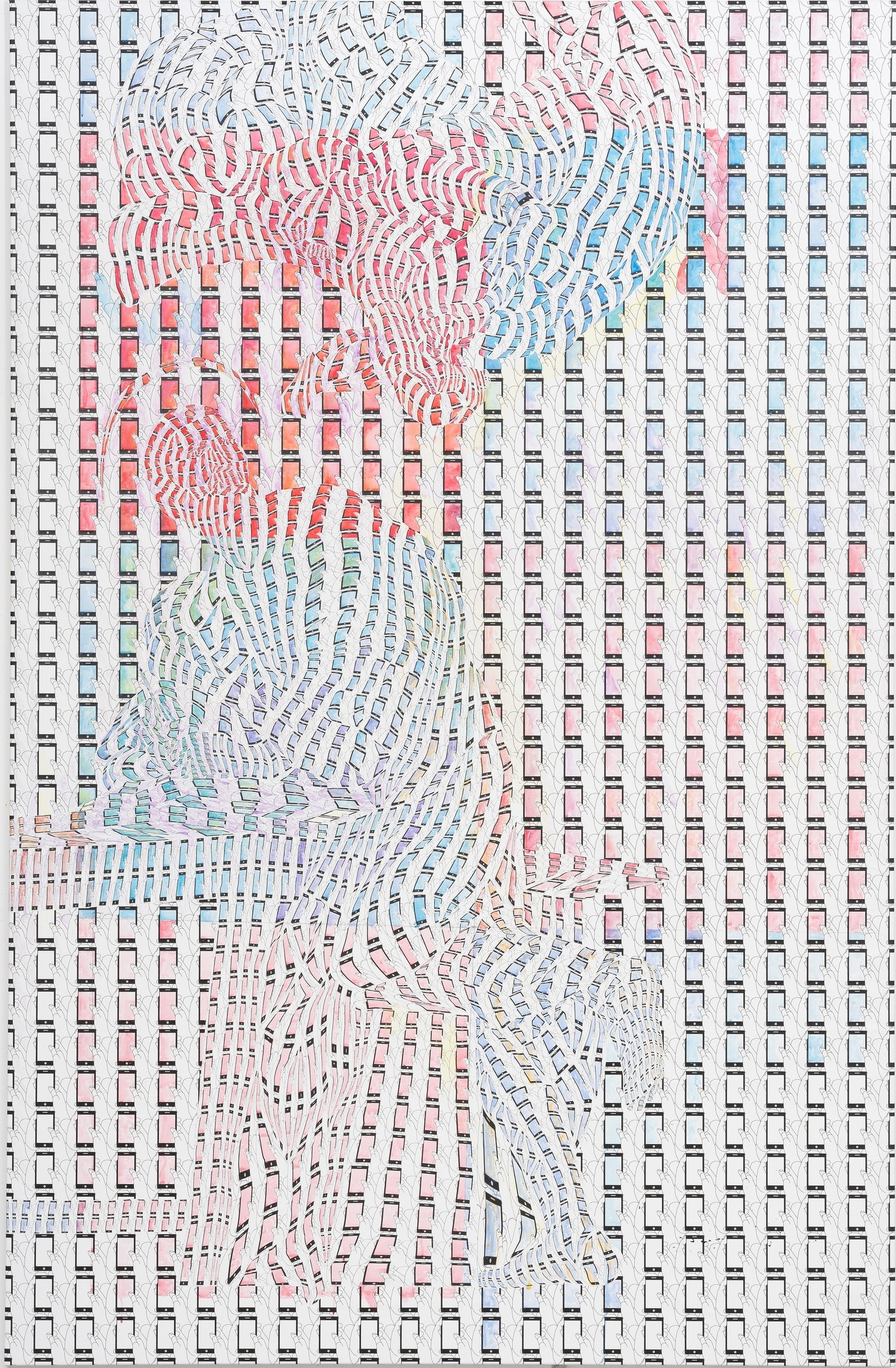

Caravaggio 3 (Zeichnung)/Hl. Matthäus trifft Engel, 2018

digital print and gouache on canvas

270 × 179 cm

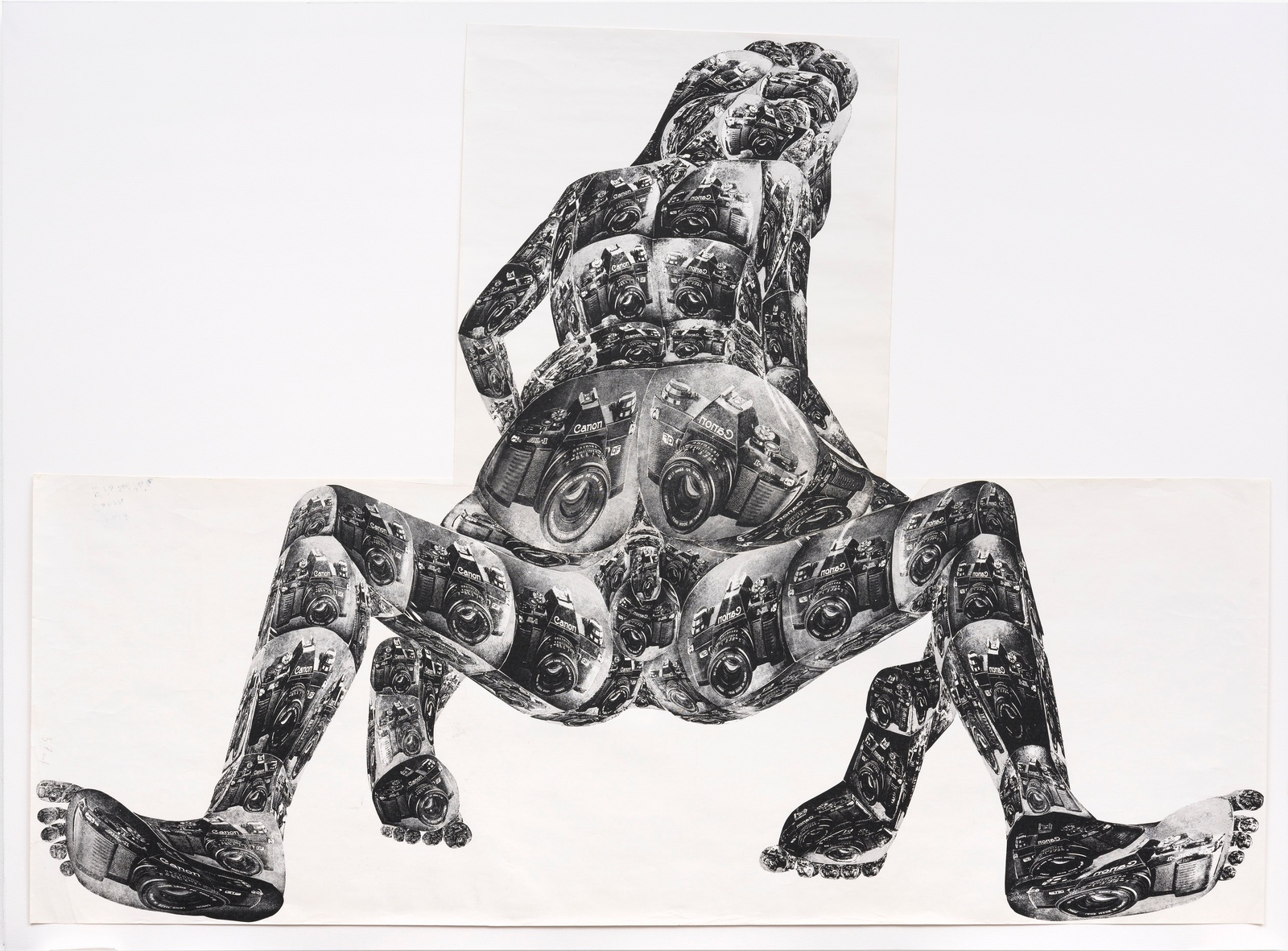

Fuck Canon, 1991

collage on paper

120 × 166 cm

For five decades now, Thomas Bayrle has investigated the technological metamorphoses of industrial and post-industrial societies, their economic preconditions and political consequences. The historical point of departure of Bayrle’s work is the commodity aesthetics of post-war capitalism, which he analyzes as a pioneer of Pop Art in Germany since the 1960s. In his work, Bayrle often uses seriality in order to create an overall image through the repetition of one motif that he individually modulates. The abstract is thereby confronted with the singular, uniformity with divergence, a confrontation by means of which Bayrle makes visible the mechanisms of mass-production and the representational forms related to it. The exhibition assembles groups of works from three decades, in which the thematic continuity of Bayrle’s approach is as much present as is the diversity of media and methods he employed over the years.

In Fuck Canon, 1991 the camera, the image-generating apparatus, becomes the constituting formal element, and the ornament is construed as the place of intervention. The passivity of the subjects – who appear in front of the camera to produce the pornographic image depicted in the overall image – is juxtaposed with an active intervention in the imaging technique. For the production of the distorted miniature motifs, several people worked collectively and manually with the image. At first, the motif was printed on latex and then put on a copy machine. Then several people manipulated this patch in order to fit the individual images into an overall form, which Bayrle had created in advance. Two aspects are thus simultaneously brought to light: the large-scale social and political consequences of technological innovations as well as the local and artistic spaces in which these developments can be taken up and altered. In the 16mm film Gummibaum (Eng.: Rubber Tree), 1993/94 the title is derived from the mode of production; again the motives were printed on a piece of latex und manually made to fit the needed shapes.

Created between 1990 and 1991, the Atari-Faces explore the possibility of digital image editing prior to the existence of software specializing in this domain. In collaboration with Stefan Mück, a computer program was developed by means of which the manipulation of the single images and their preparation for the printing process could be realized digitally. In lieu of the collective and manual work with the image, the series explores the possibilities of intervention opened up by a new technology. The genre of the portrait moreover anticipates the digital representation of the face that in subsequent years would be put into practice through digital cameras and smartphones. It is no coincidence that this phenomenon forms the object of Bayrle’s Caravaggio series. At the threshold between analogue and digital also Reiter und Pferd, 1990 is situated for which Bayrle used the same self-made software while maintaining a manual collage of the individual parts on the canvas.

In the Caravaggio works, Bayrle turns to the apparatus of our present. The design of the overall conception and the modulation of single motifs were done with a computer. The image was printed digitally on canvas and, in the case of the prints Caravaggio 2 (Zeichnung) and Caravaggio 3 (Zeichnung), complemented with gouache. Through the repetition of a myriad of iPhone images emerges Caravaggio’s San Matteo e l’angelo (1602). Inspired by a visit of the church San Luigi dei Francesi, in which this painting is on display and photographed every day by thousands of iPhones. Bayrle thematizes the ambivalence of the omnipresence of this apparatus: on the one hand as an active part in the proliferating spectacle, a spectacle in which the world and the work are no longer perceivable otherwise than through the lens of a camera. On the other, as part of a democratization of images and communication, a theme that also refers to the encounter between St Matthew and the angel depicted in Caravaggio’s painting.

Taken together, the works in fiat form a constellation that sketches a social and technological archaeology of the last decades, an archaeology that reaches to and covers our present. The contemporary moment, just as the past from which it emerges, becomes thereby legible as constituted by divergent forces, as constituted by problems and potentials, new forms of domination as well as new spaces for action and intervention. Neither affirming nor negating it unconditionally, Bayrle’s work rather makes this contemporary moment visible in its entire complexity.