Susanne Paesler

Pattern Recognition

January 25 – February 29, 2020

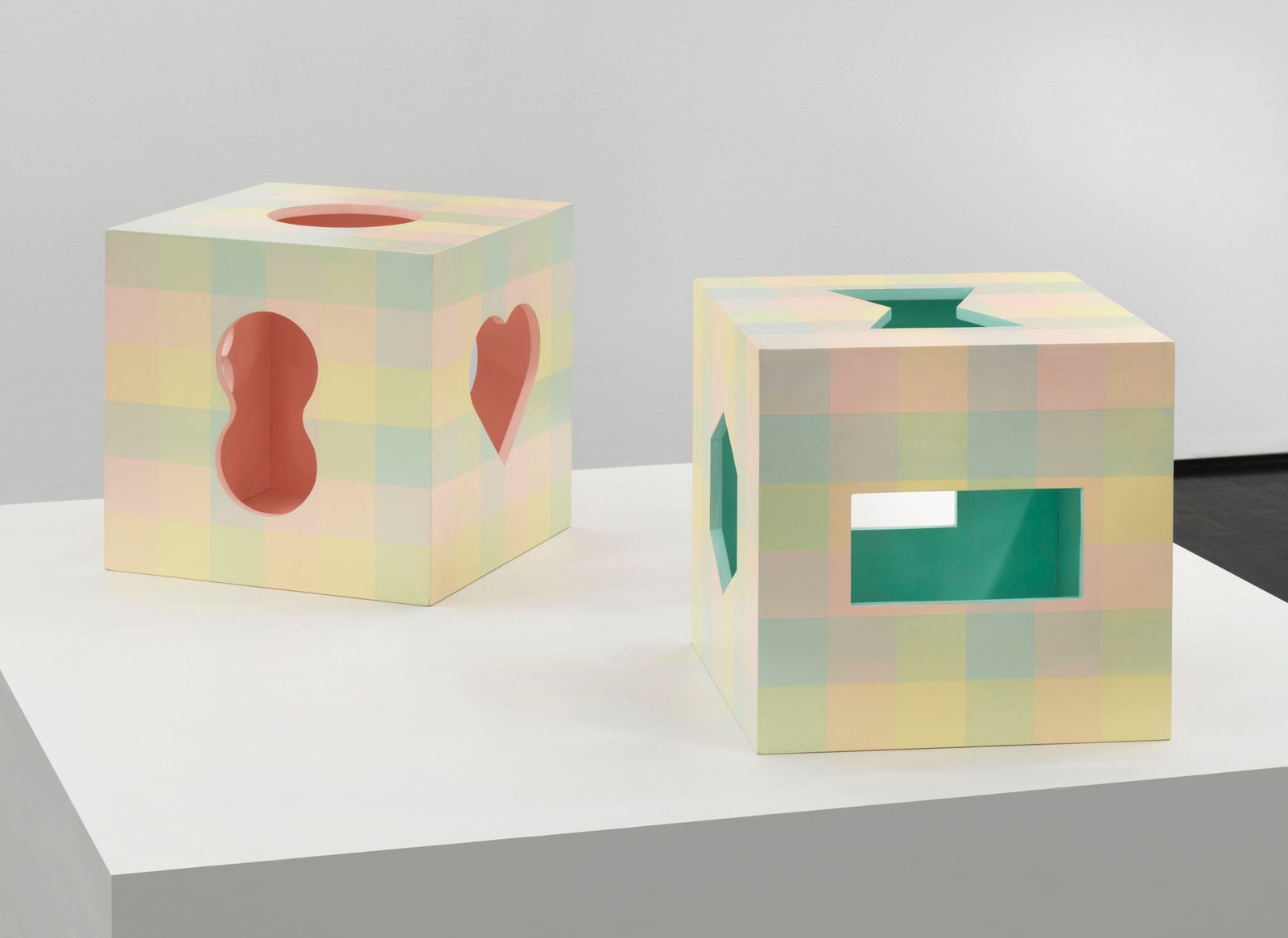

o.T., ca. 1993lacquer on MDF2 parts each 38 × 38 × 38 cm

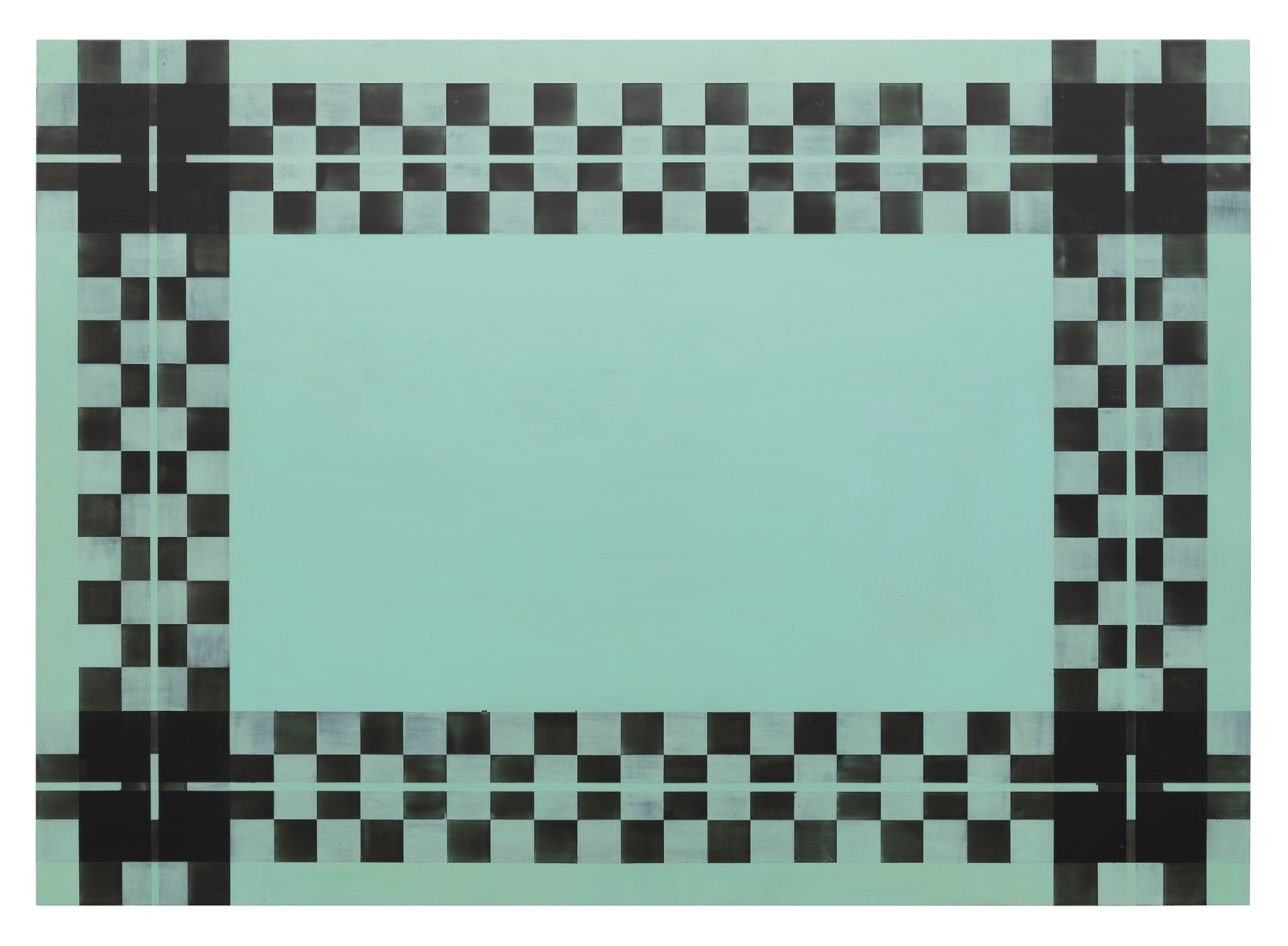

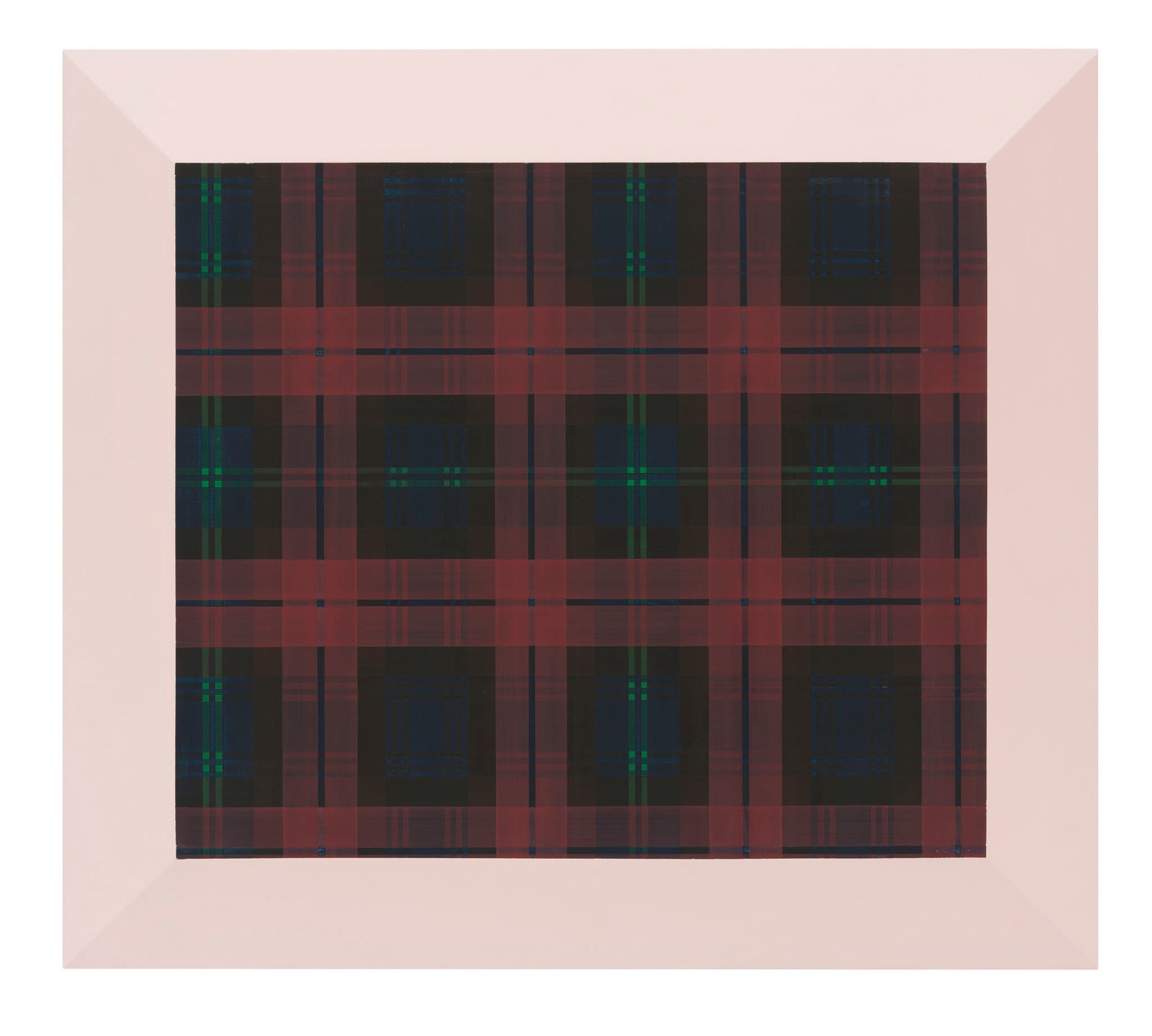

o.T., 1995lacquer on MDF, silkscreen print MDF4 parts each 71 × 80 × 4 cm

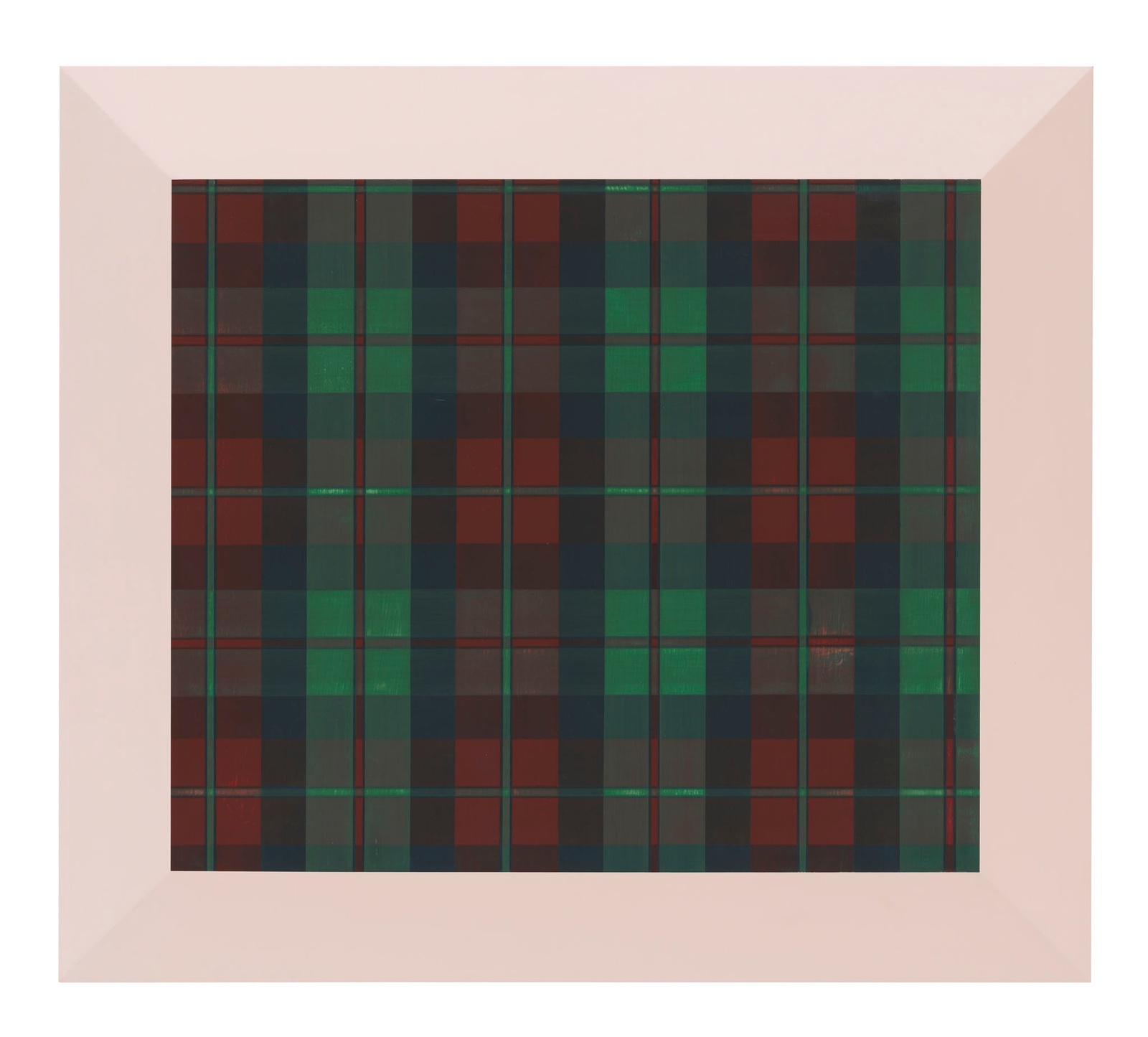

o.T., 1991alkyd colour on aluminium100 × 140 cm

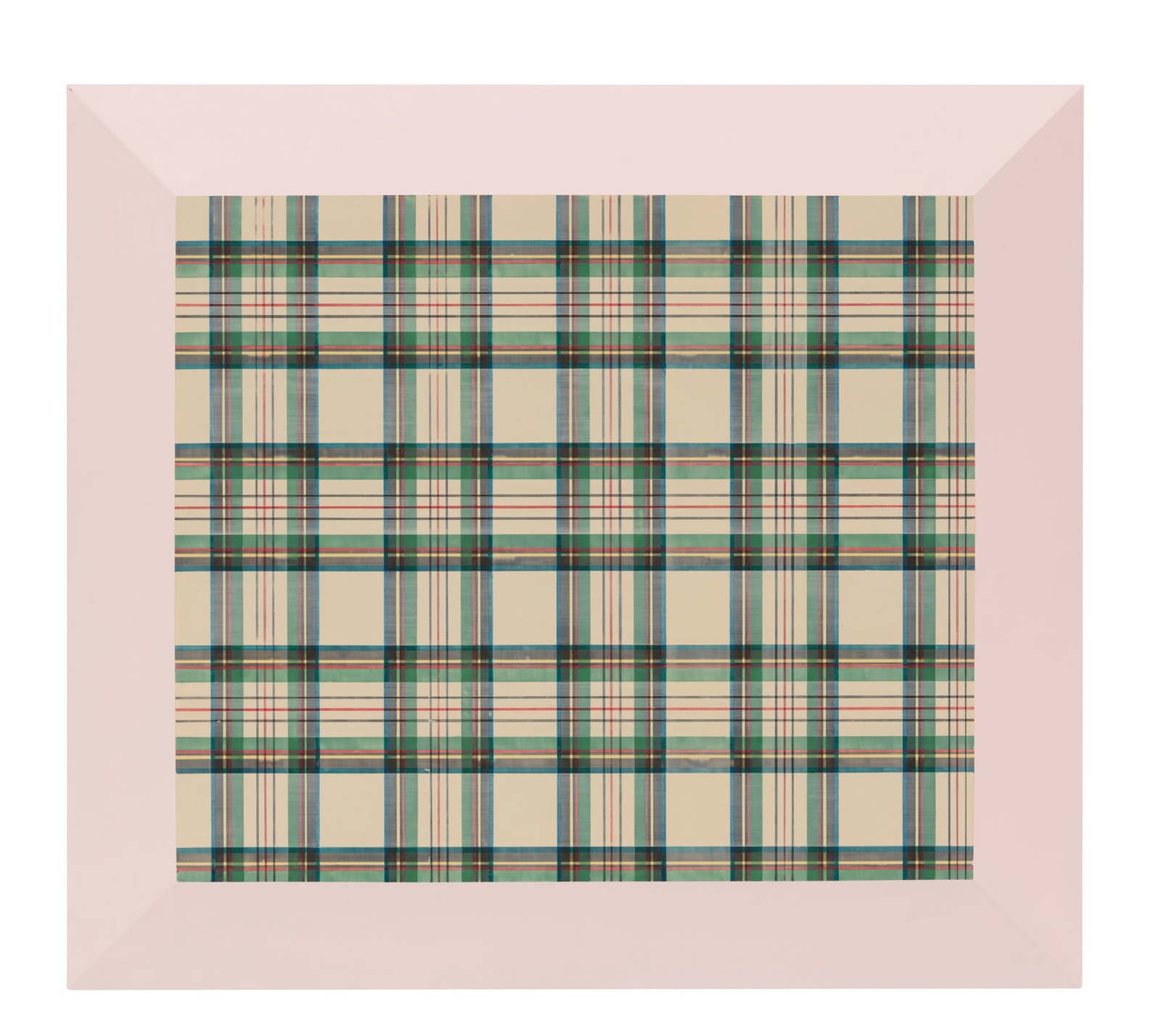

o.T., ca. 1998lacquer and foil on aluminium150 × 150 cm

o.T., 1992alkyd colour on aluminium70.4 × 125 cm

In matters of appearance

The paintings are abstract. Lines intersect and overlap to build grids. The compositions are neither calculations nor inventions. They’re based on simple observations, lifted.

These are fabric paintings. Transformed, cropped and copied patterns: argyle socks, checkered tablecloths, the Berlin U-Bahn’s camo. Paesler selected fabrics that reminded her of something.

They’re on the tip of our tongue, a blurred memory of a bourgeois jacket. There is an anecdote somewhere. Grotesque nostalgia for markers of class distinction.

The textile stands in for texture. Paesler responded to a demand for texture in painting. “Being creative,” Anni Albers argued, “is not so much the desire to do something as listening to that which wants to be done: the dictation of materials.” The textile prescribes the painting.

Paesler’s paint embellishes canvas, wood and most often, thin aluminum. Lacquer on metal like car paint, Minimal art’s hang-up on permanence. And Sherrie Levine’s chess and backgammon boards on lead.

As a technique, the pattern is a framing device that creates a limitless sequence of confined spaces. Like the fabric squares she works from, Paesler’s patterns are contained. She frames the framing device, dissects and brackets it.

“Allegorical imagery is appropriated imagery,” writes Craig Owens in Allegorical Impulse (1980), “the allegorist doesn’t invent images but confiscates them.” To copy an image is to double it. Tautologies.

Often translucent, one atop the other, Paesler’s lines are linked, concatenated (con = together + catenare = chained). Braids and chains and knitted loops are superimposed on plaid grids. Like Michelle Grabner’s paintings from crocheted blankets—subversion of the woven as a metaphor.

“It was about controlling time,” says Grabner. “The repetition, the redundancy, the predictability of these domestic backdrops.” Similarly, Paesler claimed the fittings of the early nineties middle-class. Paying attention to the familiar, she unravels and extends what it means.

Like sentences, one swath of paint is read through another. The surface becomes a palimpsest, as if the pattern and its abstraction obstruct each other, coexist.

The co-dependence of the abstract and the concrete is always at play. That’s the crux of the doubling. By transforming familiar fabrics into abstract compositions, Paesler reproduces the way in which tartans and argyles are abstract signifiers of social status. Let’s double down: Paesler’s paintings are an allegory for the abstracting codes of cultural value through which society is organized.

It is a matter of appearances.

Tenzing Barshee & Camila McHugh