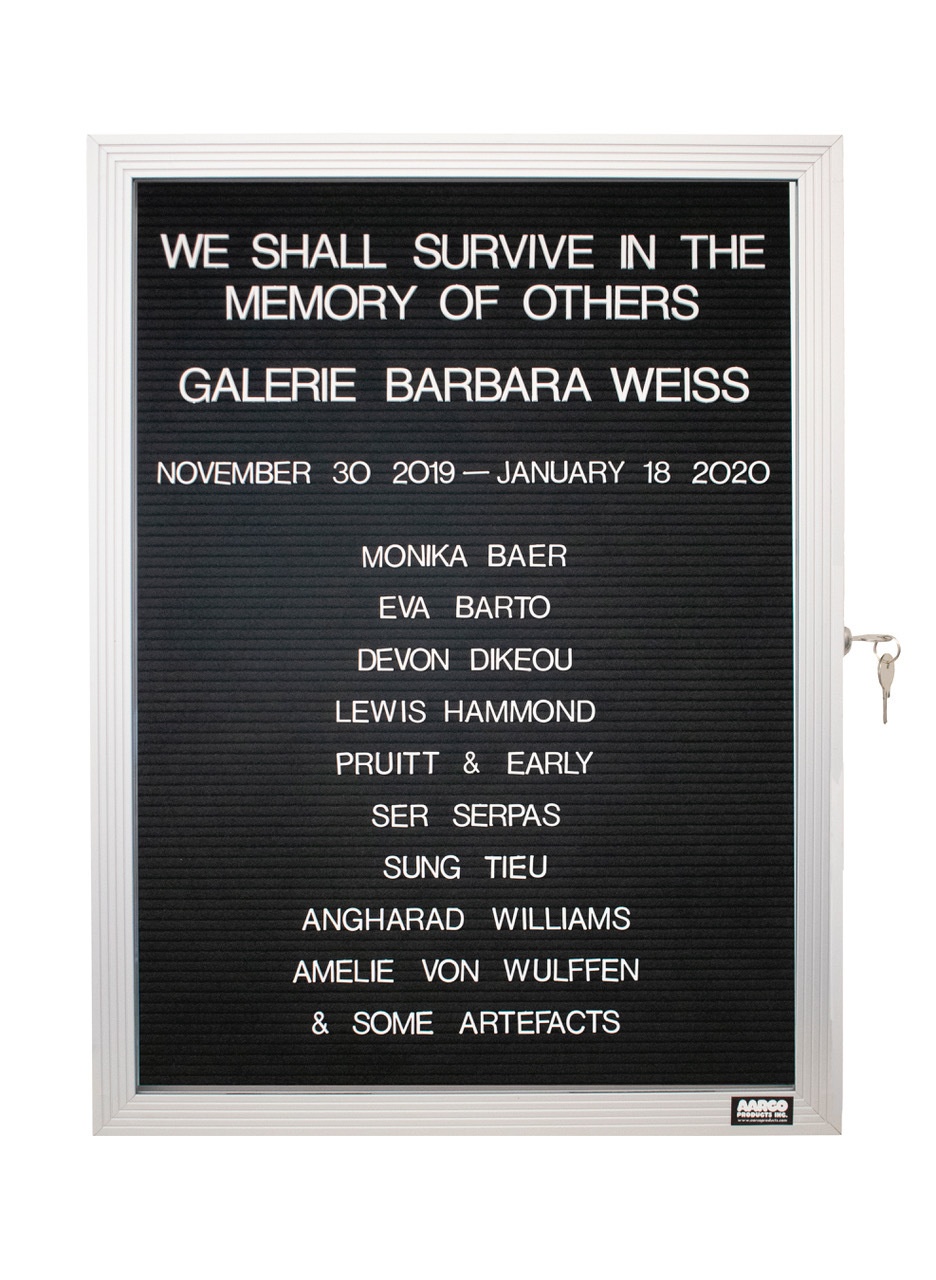

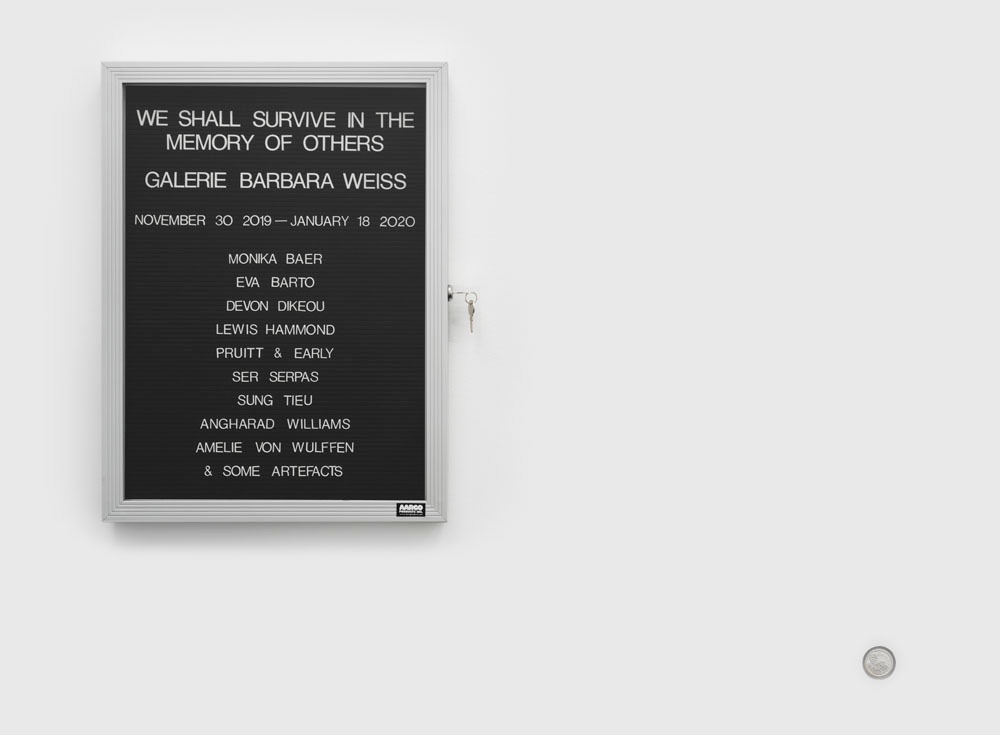

We Shall Survive in the Memory of Others

Monika Baer, Eva Barto, Devon Dikeou, Lewis Hammond, Pruitt & Early, Ser Serpas, Sung Tieu, Angharad Williams, Amelie von Wulffen

November 30, 2019 – January 18, 2020

Devon Dikeou

WHAT'S LOVE GOT TO DO WITH IT? We Shall Survive in the Memory of Others, 1991

Ongoing Lobby Directory Board Listing Artists, Gallery, Curators, Exhibition Titles, Dates, Replicating the Lobby Directory Board work table 420 West Broadway

60.96 × 45.72 cm

Silver Bullet Silver Shield Consumerism, 2014

silver coin

Ø 3.9 cm

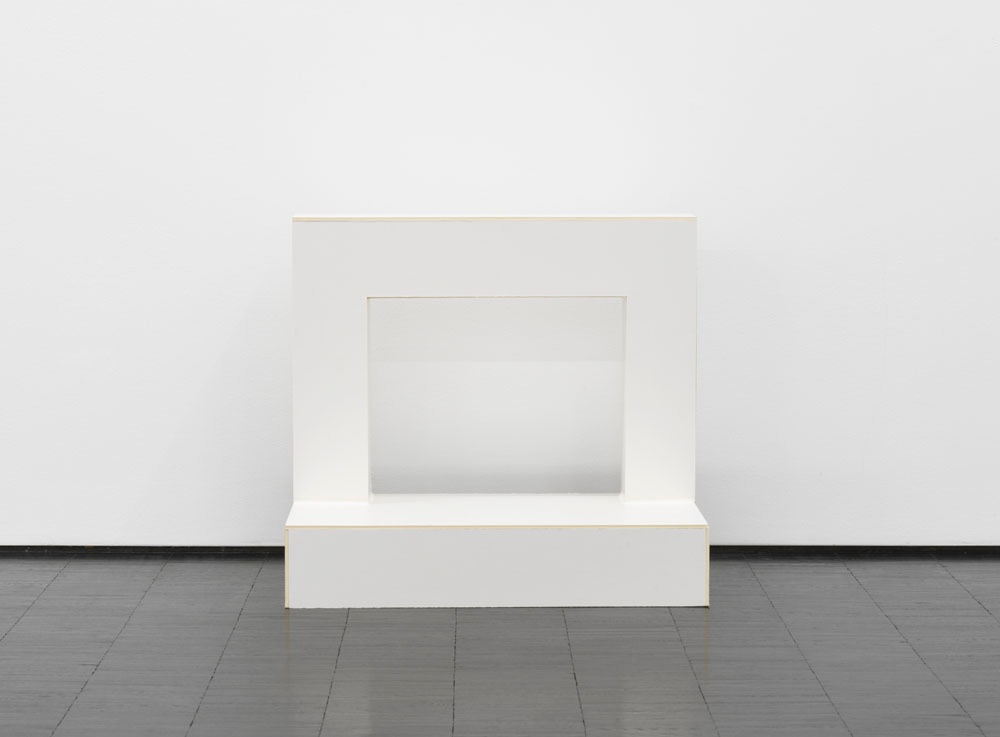

Angharad Williams

Scarecrows iii, 2018

architectural foamboard

107.5 × 140.5 × 20.5 cm

Lewis Hammond

Guillotine, 2019

oil on canvas

50 × 40 cm

Ser Serpas

despair in the guise of the jackal, 2019

glass, blinds

168 × 145 × 60 cm

Angharad Williams

Scarecrows ii, 2018

architectural foamboard

58 × 64 × 36.5 cm

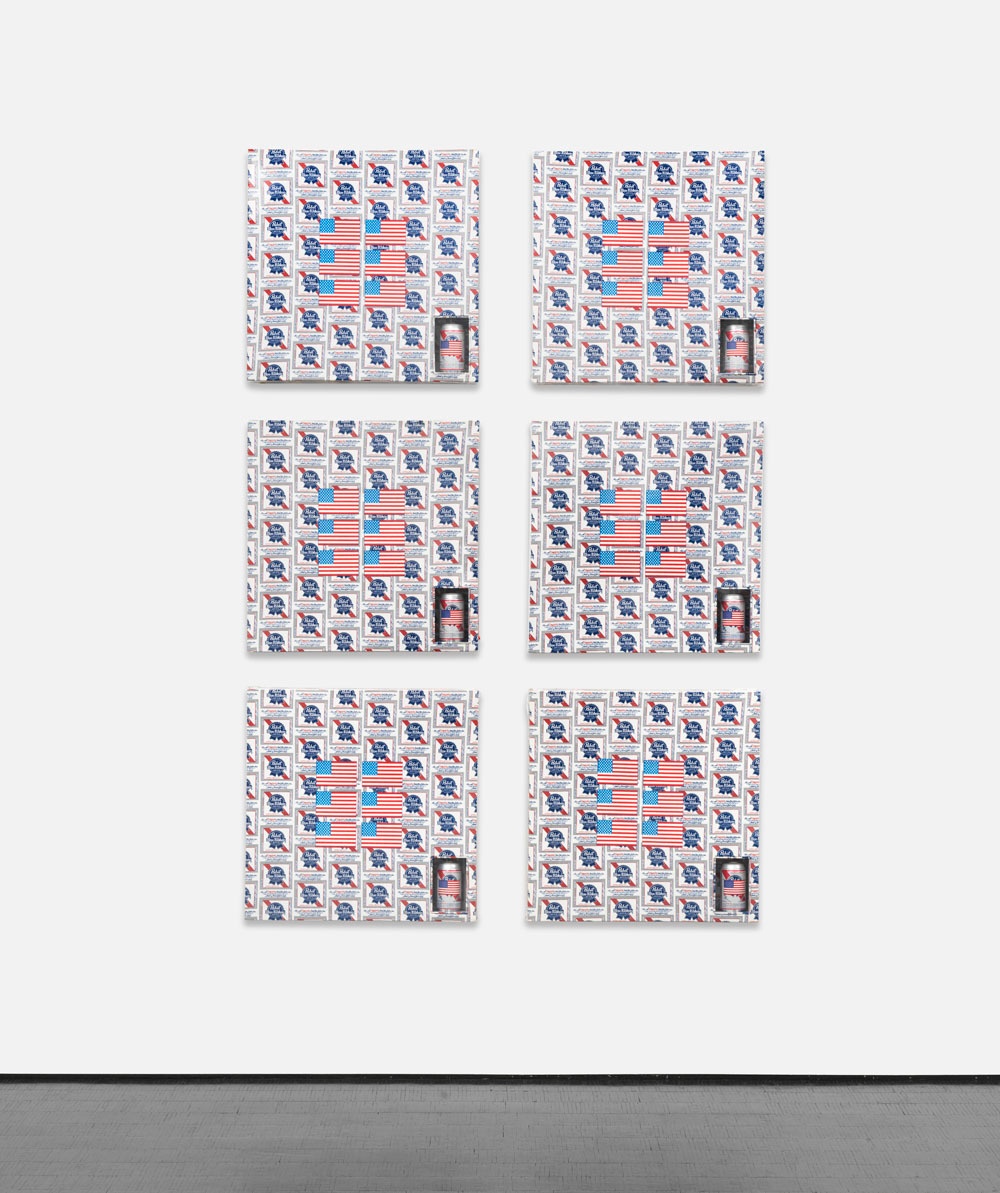

Pruitt & Early

Artwork for Teenage Boys (Pabst, American Flag Six Pack), Early 1990s

heat transfer on fabric with plastic shrink wrap, beer cans with decals, in six parts

175.26 × 116.84 cm

Pruitt & Early

Artwork for Teenage Boys (Pabst, American Flag Six Pack), Early 1990s (detail)

heat transfer on fabric with plastic shrink wrap, beer cans with decals, in six parts

175.26 × 116.84 cm

Ser Serpas

self acclimation temperature controlled, 2019

bathtub

183 × 140 × 110 cm

Ser Serpas

self acclimation temperature controlled, 2019

bathtub

183 × 140 × 110 cm

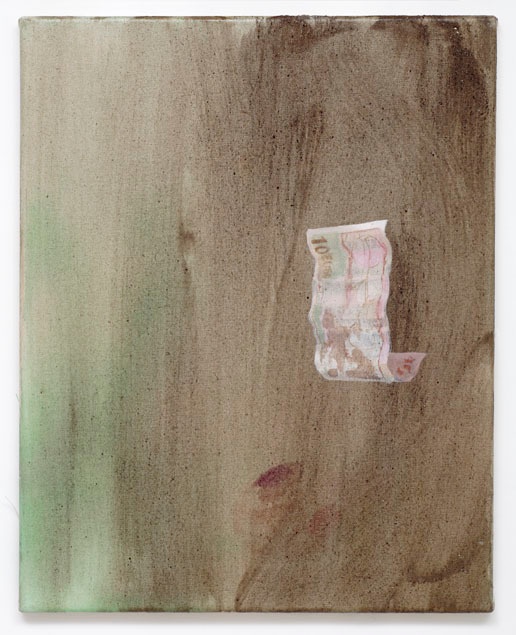

Monika Baer

10 Euro, 2005

watercolour, ashes, oil on canvas

50 × 40 cm

Angharad Williams

Scarecrows i, 2018

architectural foamboard

96 × 106 × 16 cm

Lewis Hammond

Perennial Pyre, 2019

oil on canvas

90 × 130 cm

Amelie von Wulffen

o.T., 2003

watercolour pencil on paper

21 × 30 cm

We are bound to take the narratives that turn their gaze to the past – those stories we call history – into consideration when the title of a work indicates that it dates from the “early 1990s.” It is as if this time could only be vaguely remembered, as if it was separated from us by the fog of time. A letter board assembles some basic information: a place, a time, a title, participants. The place it references – 420 West Broadway – is often mentioned, evoked as a place “where history was written.” The board in the exhibition puts all the names and places in a relation with this … maybe a futile attempt, maybe a different story. The works, however, that were made in the early 1990s bear this address on their back.

The title of the exhibition references a quote from Vilém Flusser: “We Shall Survive in the Memory of Others …” This speaks of a crucial belief, namely that there is no spirit, no soul, nothing that survives death. It is only in the memory of others that we can live on. Living on, then, means being subject to change and exchange, to dispersal and dependency, beyond control and intention. My memory depends on others, and their memory depends on me. Our narratives are precarious.

In the early seventeenth century, a frequent motif in glass paintings were the Four Doctors of the Church – Pope Gregory, St Augustine, St Ambrose and St Jerome (Hieronymus). Their names appear at the bottom of the image, set in an architectural frame or cartouche. Much later, around the middle of the twentieth century, these glass paintings were taken out of their context, cut and set in lead to build this lantern. As far as we can tell, the picture of Jerome – usually depicted with his cardinal’s hat, sitting in his study translating the bible into Latin – is absent. He has been replaced by an archer on the left and a different figure on the right.

Sometime around 1800, a sailor – probably from a Dutch Colonial context, on the route to East India –made himself a chair. At least this is what we assume. The chair also contains a little chest. We don’t know the sailor, his name is lost. A stranded object. But the figures and patterns allow to place it in its context, however roughly. There are ivory Kris handles with fairly similar floral decorative patterns. And certain ivories from Sri Lanka that were taken to Denmark have lion’s heads akin to the chair. Sadly, all the reference books were sold.

Maybe the most persistent myth in our time is that whoever is depicted on your notes and coins guarantees its value, that symbolic representation can ground the economic. For some, that means security. For others, it means utmost dependency and decadent fraud, a scheme that is inevitably bound to shipwreck. On a canvas, we see a 10€ note disappearing, disintegrating into the materiality of paint.

Elsewhere, a different myth of the ground is evoked against the immateriality of the symbolic: that precious metals guarantee value independent of the authorities and context. Once narration overcame the limits of the image, it introduced a set of symbols that could be transmitted irrespective of their material basis. Today, the image is very agile, too, but to be so it had to be translated into a code – .jpgs can travel the internet, oil on canvas can’t.