Don Quixote

Heidi Bucher, Andrea Büttner, Larry Clark, Peter Fend, Dorota Gawęda & Eglė Kulbokaitė (Young Girl Reading Group), Jonathan Horowitz, Crispin Oduor Makacha, Jannis Marwitz, Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo), Cameron Rowland, Elaine Sturtevant

January 20 – March 3, 2018

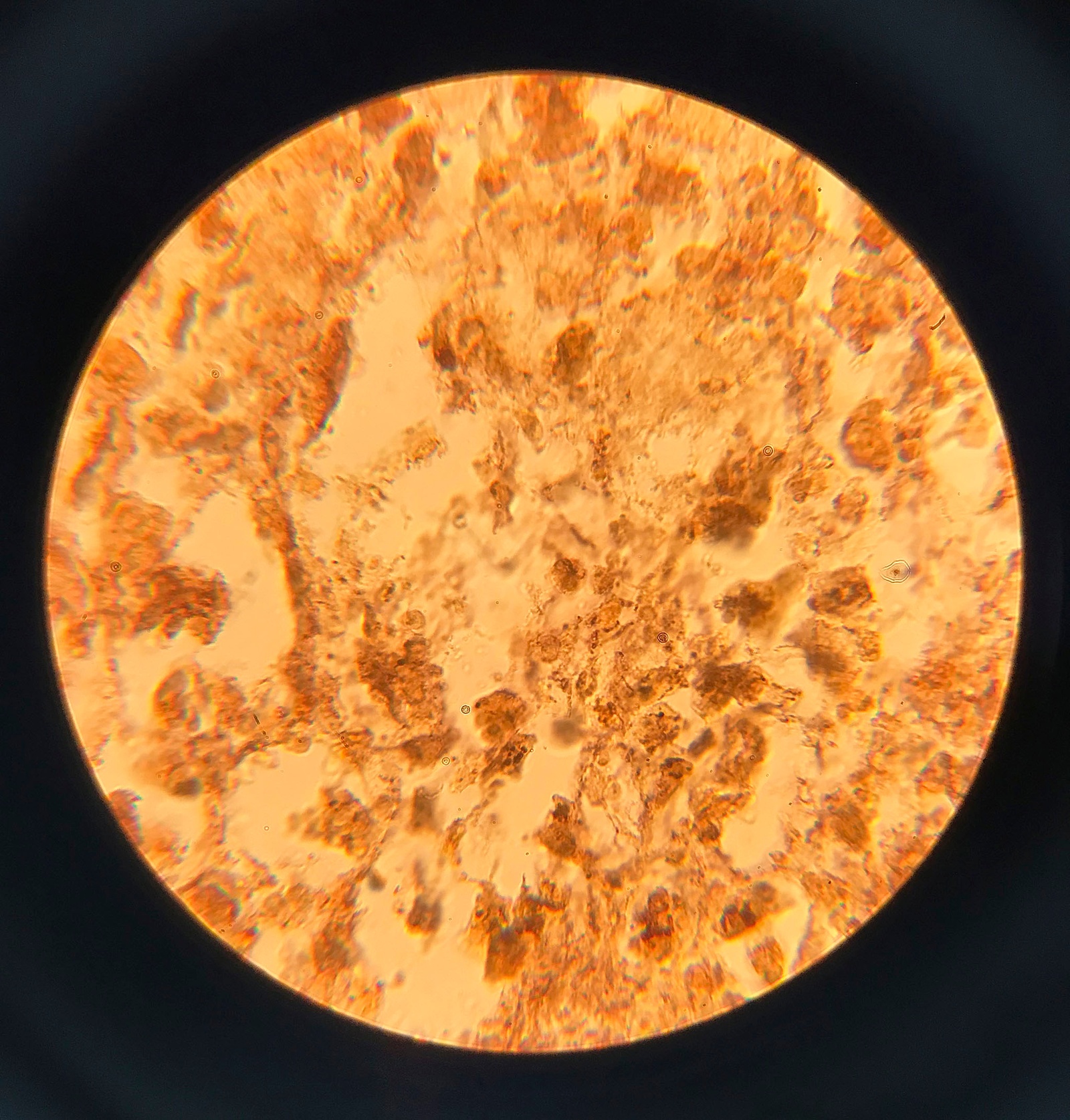

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo)

Treponema pallidum (Syphilis), 2018

glass, treponema pallidum, Bresser Erudite microscope

32 × 20 × 10 cm

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo)

Treponema pallidum (Syphilis), 2018

glass, treponema pallidum, Bresser Erudite microscope

32 × 20 × 10 cm

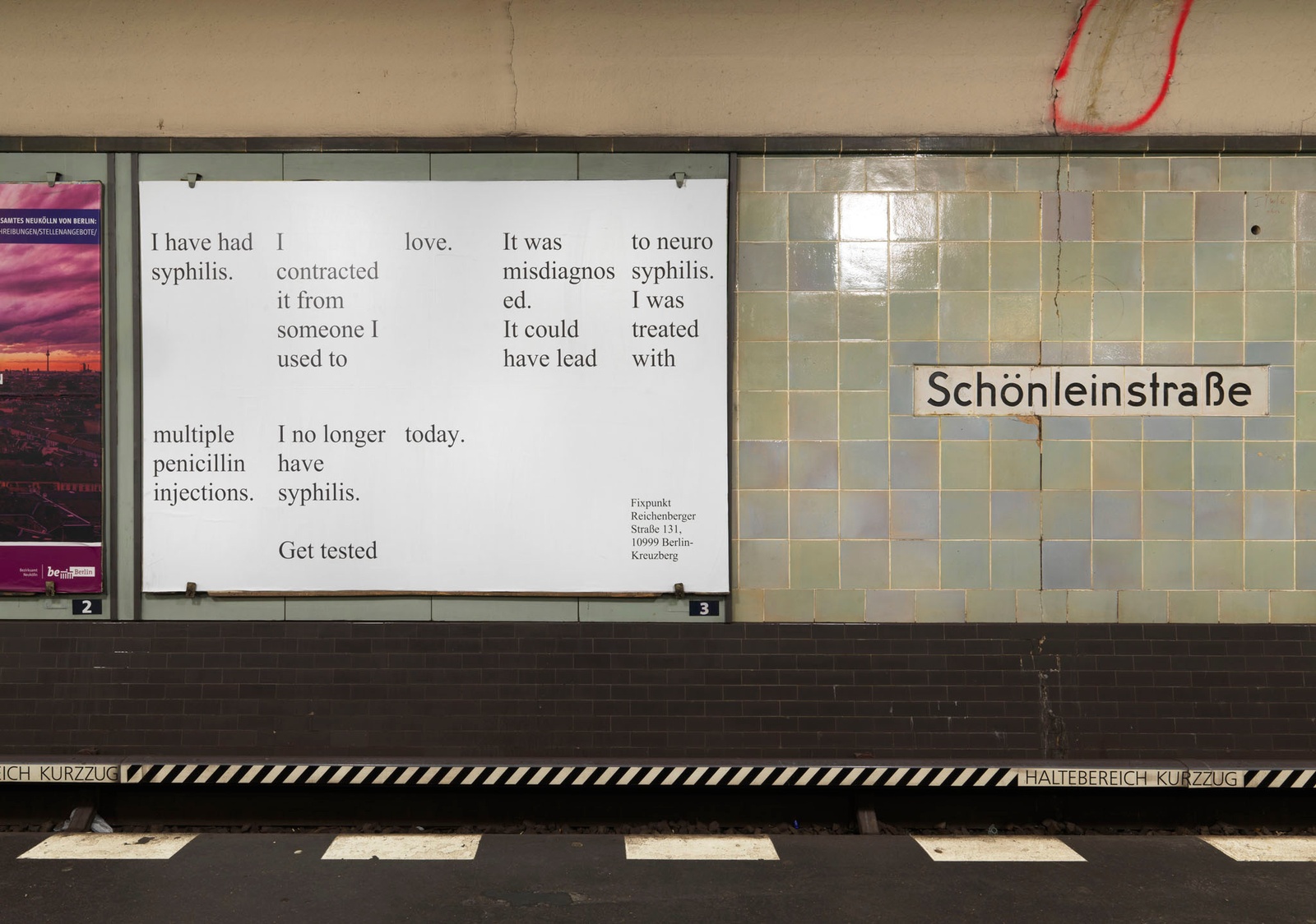

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo)

Get tested today. (Lass Dich heute testen.), 2018

public advertisement at the subway station Schönleinstraße

dimensions variable

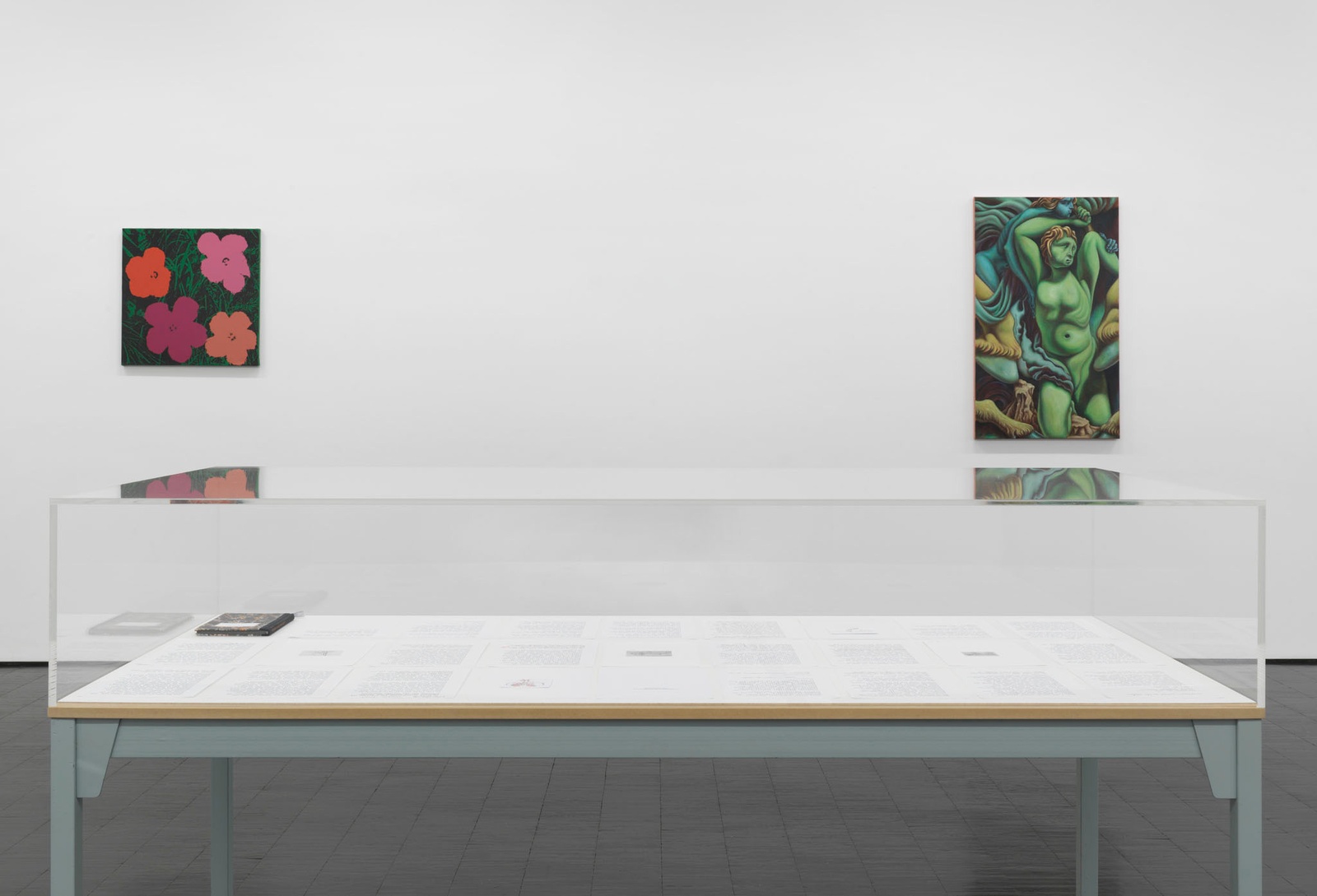

Materials related to Christian Leigh

publications, books, magazines

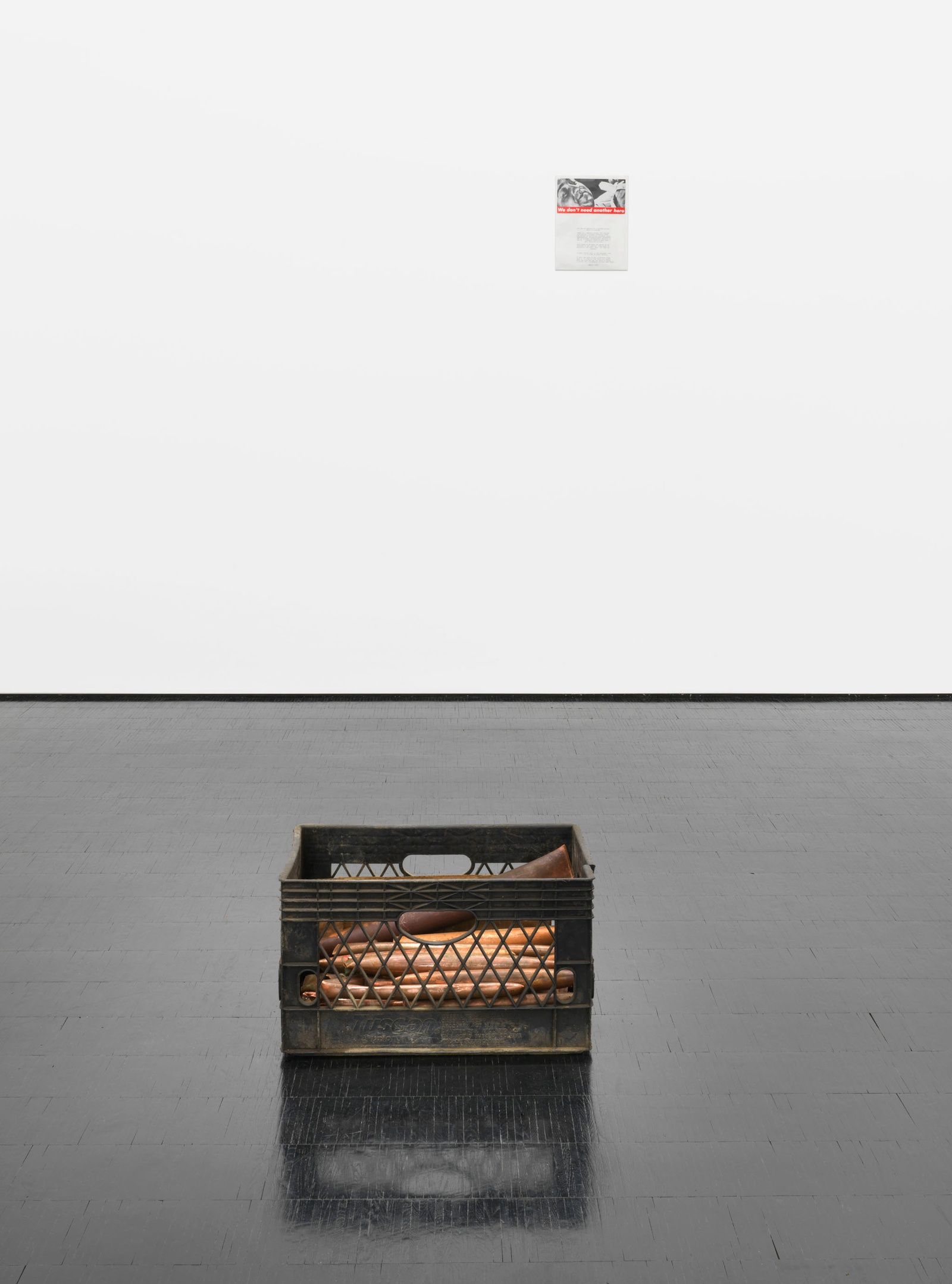

Cameron Rowland

Loot, 2018

Cut copper tube, cardboard box, crate

27 × 48 × 33 cm

rental

Peter Fend

We don ́t need another hero, 1988

invitation card on paper

28 × 22 cm

Heidi Bucher

Schindelfenster, 1988

textile and latex

280 × 280 cm

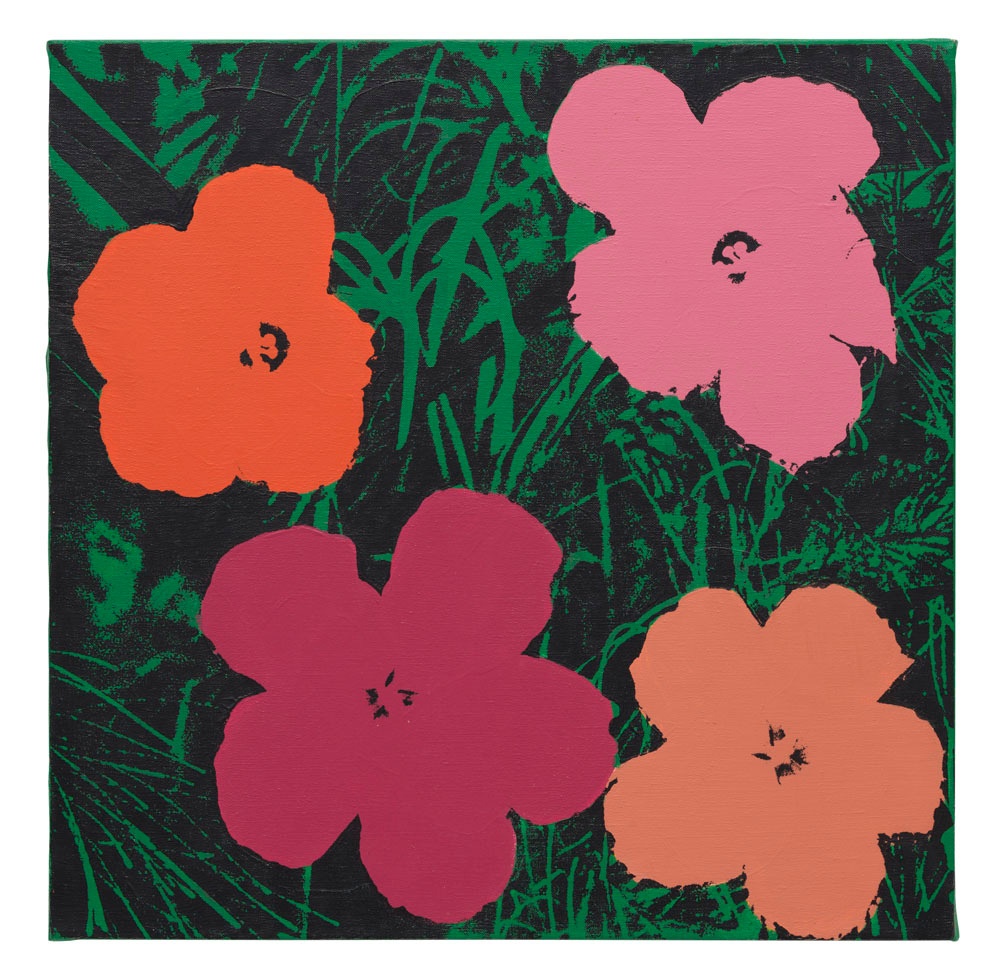

Sturtevant

Warhol Flowers, 1965

silkscreen print

58 × 55 cm

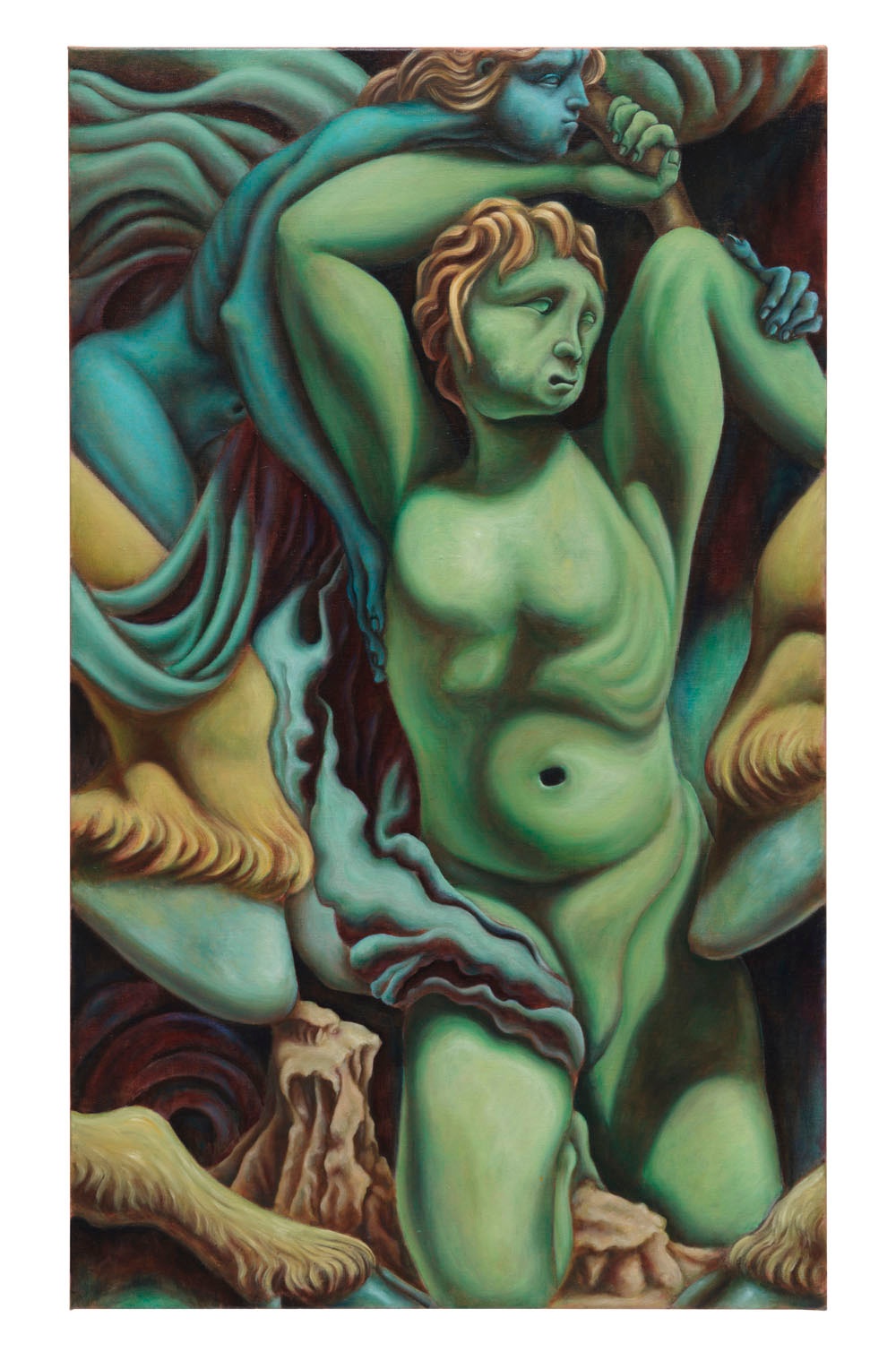

Jannis Marwitz

Untitled, 2018

oil on canvas

100 × 60 cm

Andrea Büttner

Tuffstein, 2018

tuff stone, moss

dimensions variable

Miguel de Cervantes composed – with a strict economy of means – the two volumes of his novel as a complex web in which his personal situation, the socio-political context, and formal innovations interweave. Cervantes did not only introduce an astounding level of self-reflexivity, he also created a reservoir of strategies from which some of the most influential ideas in the arts and literature of the 20th Century could be extracted.

The first volume of Don Quixote is – factually and and allegedly – constituted of fragments, translations, and the use of materials written by others. For want of such acquittances, Cervantes had to write the eulogies from befriended writers and patrons, which were a common part of a book’s preface at the time, by himself. But it is already here that one can find more ingenuity than in most books. In the preface, Cervantes presents the ensemble of his tricks to the reader: would-be citations, which nobody wants to check anyways, eulogies from imagined bishops, and generally the use of “Latin glitter.” And all of this is recommended to him by a friend who finds him pondering over the preface. In the actual novel, the most striking break occurs in chapter XIX: the plot is interrupted and only taken up again after the narrator accidentally finds an Arabic manuscript by the historian Cide Hamete Benengeli, a manuscript that turns out to be the missing part of the novel. Here, the novel’s political dimension becomes apparent for the first time: at a time in which hundreds of thousands of Muslims were expelled from Spain, Cervantes based his entire novel on an Arabic manuscript.

The first volume was a great success with the public. But even before Cervantes had finished the second volume, a certain Alonso Fernanéz de Avellaneda – a pseudonym whose identity could never be clarified – published a sequel to the novel. Cervantes, who confronts the knight and his squire at the beginning of the second volume with the existence of the first, had thus to meet another challenge. In the second part of the novel, Don Quixote and his squire constantly meet persons who have read the first volume. Every encounter turns into a comparison and Don Quixote’s own story takes the place of the romances of chivalry that served as a model. After Cervantes got to know about the sequel to his book, he also took it up in the continuation of the story: not only does Don Quixote have to meet the expectations that resulted from the first part; he also has to fight constantly against Avellaneda’s defamations.

Unlike many of his peer writers, Cervantes couldn’t work on the basis of economic security. Throughout his life he dreamt of success as a writer, while he had to cope with setback after setback in his day jobs and was barely able to write at all. He was a soldier, in slavery in Tunis for five years, a tax collector and a prisoner; but there are also longer periods in his life not much is known about, where he probably just drifted around, hustling for his daily bread. However, Cervantes could and would never – and this is a certain structural parallel to the life of the novel’s hero – give up the pretense of respectability, however much it might have crumbled. Never would he accept that he had not been predestined for a literary career. At the beginning of Don Quixote, there is a chosen identification, expression of the longing for another life. And the Knight of the Sad Countenance eventually finds this life, even though nobody except him is able to see it.

Cervantes wrote the two volumes of his novel at the end of his life in a climate of political regression. After a period of religious tolerance in the 16th Century, Spain began, in the wake of the counter-reformation, to systematically persecute people of other denominations. The arts and sciences were wedged by doctrine and surveilled by the inquisition. Today, in a time where questions of ethnic, sexual and religious affiliation, of political regression and economic precariousness have condensed into a climate of depression, this exhibition attempts to link the novel Don Quixote and its author with artistic practices that operate beyond essentialist and territorial rhetoric. The artists in this exhibition made a leap in reaching out to fields that they weren’t born into, but chose to engage with. They did so by using images, objects, procedures, strategies or feelings that already floated around them. When something is taken up, the notion of theft is never far away. Yet, resignifying, refunctioning, and repeating are much more often acts born from desperation and destitution. They are the self-authorisation of those to whom no resources, no symbolic language was given. Taking up something they were lacking and putting it to a different use, these practices subvert established structures from within.